For Rachel’s son, this began in the most ordinary way – gaming.

He started playing Roblox offline when he was eight or nine. Eventually, he wanted to play online with friends they’d moved away from.

Later, like many gamers, he found Discord, a platform where he wanted to share “hacks” and tips.

“I always felt like he was safe,” she says.

Rachel says she was unaware of the risk her son faced

Rachel says she was unaware of the risk her son faced

But slowly, underneath the surface, things changed.

His behaviour – moodiness and withdrawal – looked like typical adolescence.

When his phone was confiscated at school Rachel and her husband checked his room.

What they discovered shocked them.

“We found a lot of razor blades,” she says. “Pocket knives. Folding knives we’d never seen before. Kitchen knives hidden away in little boxes.”

When he finally handed over the password to his phone, everything clicked into place.

There were hundreds of memes. At first glance they were pastel and cartoonish, Hello Kitty‑like, anime‑ish.

But up close, each held something wrong: a smeared black eye, blood from a socket, bloodied skin.

Captions read: “I don’t matter”, “I’m worthless”, and “Make me bleed and tell me how pretty I look.”

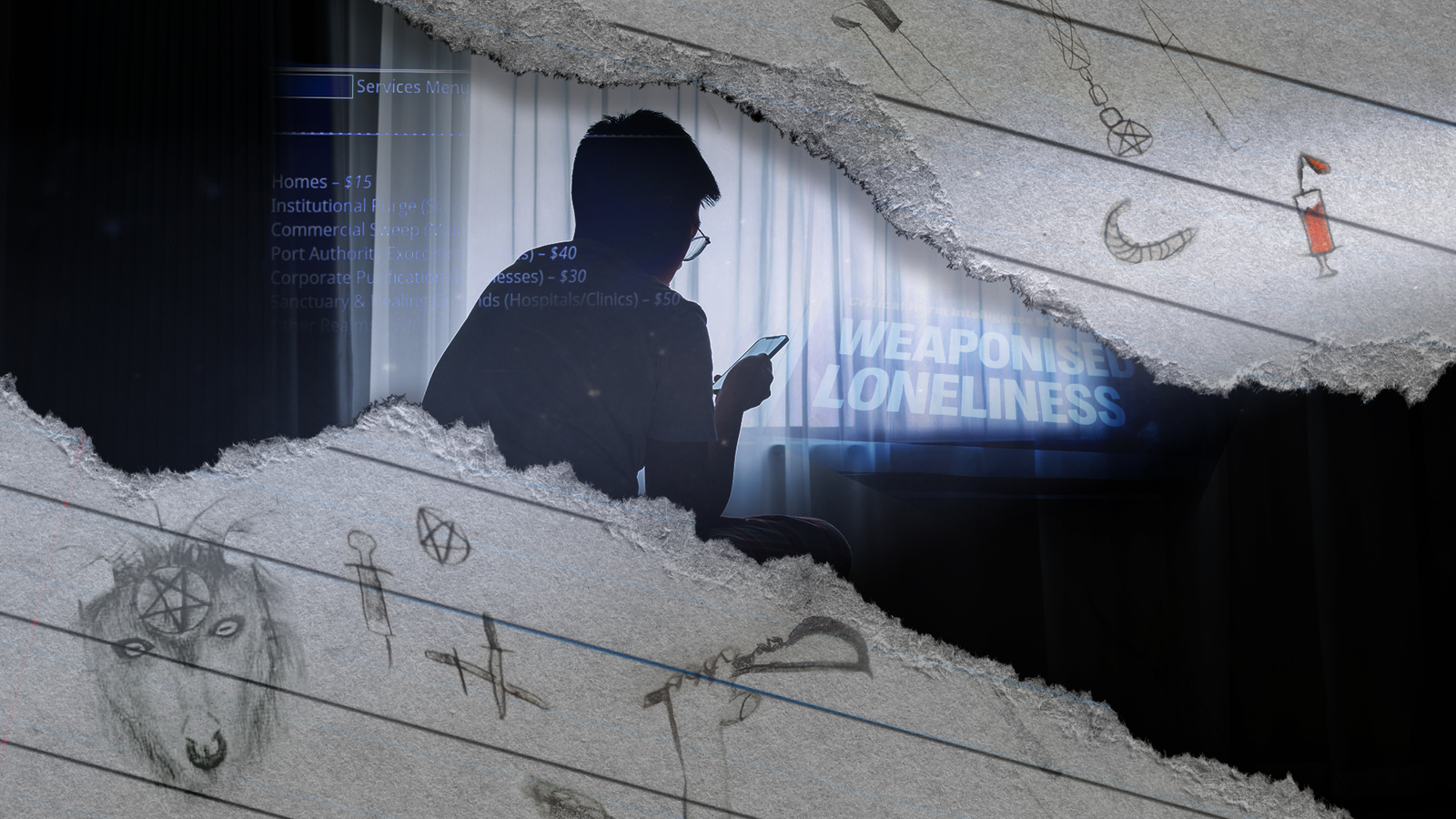

Drawings from the boy’s sketchbook

Drawings from the boy’s sketchbook

Some of the self‑harm on his body, Rachel realised, had been done “for somebody”.

She later learned this pattern is familiar to the Com.

Her son was exposed to mental health language, then anorexia‑style content, then self‑harm, then sexualised content.

Ten months of escalation.

One of the people communicating with him, she believes, was from Croatia – a reminder that this threat is everywhere.

Her son is neurodivergent, “an extra vulnerability”, and was searching for a place to belong.

Online, he found a community that seemed accepting.

But belonging came with conditions.

A meme Rachel discovered on her son’s phone

A meme Rachel discovered on her son’s phone

Eventually, Rachel and her husband removed everything – their son’s smartphone, all apps, and his bedroom was moved closer to them.

Now he has a flip phone with no internet. He games only with school friends. His parents monitor everything.

He’s now in “a great space,” Rachel says. But he still cannot talk about what happened.

Once, he corrected her: “I wasn’t in a cult. I was being groomed.”

Rachel fears her son saw more harmful content not stored on his device

Rachel fears her son saw more harmful content not stored on his device

Rachel’s guilt still lingers.

“I don’t think I saw everything that he saw,” she says. “I don’t think I heard everything he heard.”

“I allowed his world view, during this really critical period between 10 and 13, to be developed meme by meme, line by line, text by text.”